Java Advanced Topics Study Notes

Table of Contents

Annotations

Annotations in Java are like labels or notes you add to your code. They give extra info to the compiler, tools, or frameworks. They don't change how the code works but help in understanding or processing the code better. Introduced in Java 5, they are widely used in modern applications like web development, frameworks (Spring, Hibernate), and Android.

What Are Annotations?

- They start with '@' symbol, like

@Override. - You can use them on classes, methods, variables, parameters, or even other annotations.

- They are metadata (extra information about your code).

class Parent {

void show() {

System.out.println("Parent show");

}

}

class Child extends Parent {

@Override // This annotation checks if we're correctly overriding

void show() {

System.out.println("Child show");

}

}

Here, @Override tells the compiler: "I'm changing the parent's method." If you spell

show wrong, it warns you.

Built-in Annotations

- @Override: Checks if a method is overriding a parent method.

- @Deprecated: Marks old code that shouldn't be used anymore.

- @SuppressWarnings: Ignores compiler warnings.

Detailed Explanation with Code

1. @Override

class Animal {

void sound() {

System.out.println("Animal sound");

}

}

class Dog extends Animal {

@Override

void sound() { // compiler ensures method matches parent

System.out.println("Dog barks");

}

}

Why use? Prevents mistakes. Without @Override, if you accidentally write

sounds() instead of sound(), it won’t override – just create a new method.

2. @Deprecated

class OldCode {

@Deprecated

void oldMethod() {

System.out.println("Old logic");

}

}

class Test {

public static void main(String[] args) {

OldCode oc = new OldCode();

oc.oldMethod(); // Compiler shows warning

}

}

Why use? Tells other developers: "Don’t use this method anymore, there’s a better way." Useful when updating libraries or frameworks.

3. @SuppressWarnings

import java.util.*;

class WarningExample {

@SuppressWarnings("unchecked")

void demo() {

List list = new ArrayList(); // Raw type (usually gives warning)

list.add("Hello");

System.out.println(list.get(0));

}

}

Why use? Sometimes warnings are unnecessary. This annotation hides them, but use carefully — it may hide real issues.

Other Useful Annotations

- @FunctionalInterface: Marks an interface with only one abstract method (used in Lambda expressions).

- @SafeVarargs: Suppresses warnings for varargs with generics.

- @Retention, @Target, @Inherited: Meta-annotations (used when creating your own annotations).

RegEx (Regular Expressions)

RegEx is used to find, match, or replace parts of strings using patterns.

In Java, it is available in the java.util.regex package (classes: Pattern and

Matcher).

Basics

- Pattern: The rule you want to search (e.g.,

"\\d+"→ numbers). - Matcher: Applies the pattern to a string.

- Common Symbols:

.→ any one character*→ zero or more+→ one or more\\d→ digit (0-9)\\w→ word (letters, digits, _)^→ start of text$→ end of text

import java.util.regex.*;

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

String text = "I have 5 apples and 10 oranges.";

Pattern p = Pattern.compile("\\d+"); // pattern for numbers

Matcher m = p.matcher(text);

while (m.find()) {

System.out.println(m.group()); // prints 5 then 10

}

}

}

Useful Methods

find()→ finds next matchgroup()→ gets matched valuematches()→ checks if whole string matches patternreplaceAll()→ replace text

Example:text.replaceAll("\\d+", "X")→ "I have X apples and X oranges."split()→ split string

Example:"a,b,c".split(",")→ ["a","b","c"]

String email = "test@example.com";

if (email.matches("^[\\w.-]+@[\\w.-]+\\.[a-z]{2,}$")) {

System.out.println("Valid email");

}

Common Uses: Form validation (emails, phone numbers), extracting data, search & replace.

\\d for numbers

or \\w for words.

Threads

Threads let your Java program do many tasks at the same time, like multitasking. This is concurrency. Uses

java.lang.Thread and java.util.concurrent.

Basics

- Thread: Small task in a program. All share same memory.

- Main Thread: Starts with

main()method. - Make Threads:

- Extend Thread:

class MyTask extends Thread {

public void run() { // Code here runs in thread

System.out.println("Task running");

}

}

MyTask t = new MyTask();

t.start(); // Start it

2. Use Runnable (better):

class MyRun implements Runnable {

public void run() {

System.out.println("Run task");

}

}

Thread t = new Thread(new MyRun());

t.start();

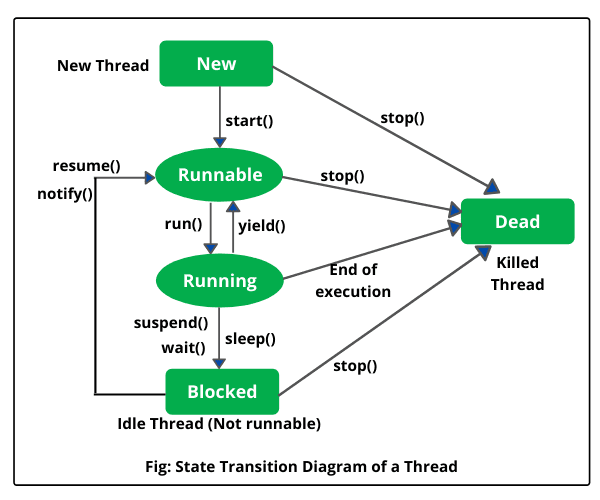

Thread Life

- New: Made but not started.

- Runnable: Ready after

start(). - Running: Doing

run(). - Blocked: Waiting for something.

- Timed Waiting: Sleeping.

- Terminated: Done or error.

Key Methods

start():Begins thread.run():The work (don't call directly).sleep(1000):Pause 1 second.join():Wait for thread to end.interrupt():Ask to stop (thread checks itself).

Sharing Data Safely (Synchronization)

- Problem: Threads can mess up shared variables (race condition).

- synchronized: Lock so one at a time.

int count = 0;

synchronized void add() {

count++;

}

- Lock: Better control.

import java.util.concurrent.locks.*; Lock lock = new ReentrantLock(); lock.lock(); count++; lock.unlock();

- volatile: Makes variable always fresh for all threads.

- wait()/notify(): Threads talk, like "wait till ready".

Lambda Expressions

Lambdas were introduced in Java 8. They are a short way to write code (functions) without creating a full class. They work only with Functional Interfaces (an interface with exactly one abstract method).

Basics

- Syntax:

(parameters) -> { body } - Example:

(int x) -> x * 2// doubles a number - No braces if one line:

() -> "Hi"

@FunctionalInterface

interface Add {

int sum(int a, int b);

}

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Add adder = (a, b) -> a + b; // Lambda instead of writing a class

System.out.println(adder.sum(3, 4)); // Output: 7

}

}

Where to Use Lambdas?

- With Lists:

list.forEach(s -> System.out.println(s)); - With Sorting:

Collections.sort(list, (a, b) -> a.compareTo(b)); - With Streams:

list.stream().filter(n -> n > 0).count();

Sorting in Java

Sorting means arranging data in order (like A→Z or small→big). In Java, sorting can be done in two ways:

Basics

- Arrays:

Arrays.sort(array); - Lists:

Collections.sort(list);

1. Comparable (Natural Sorting)

If you want objects to be sorted in their natural order (like names alphabetically), the class

should implement Comparable.

class Fruit implements Comparable{ String name; Fruit(String n) { name = n; } @Override public int compareTo(Fruit other) { return this.name.compareTo(other.name); // A-Z order } } List fruits = new ArrayList<>(); fruits.add(new Fruit("Banana")); fruits.add(new Fruit("Apple")); fruits.add(new Fruit("Mango")); Collections.sort(fruits); // Sorts by name

Why? Comparable is used when the class itself has a default way to compare objects.

2. Comparator (Custom Sorting)

If you want different ways to sort, use Comparator.

ComparatorbyLength = (f1, f2) -> Integer.compare(f1.name.length(), f2.name.length()); fruits.sort(byLength); // Sorts by name length

Why? Comparator is flexible – you can define multiple custom sorting rules without changing the class.

Simple Example

Sorting numbers in descending order:

Listnums = Arrays.asList(3, 1, 4); nums.sort(Comparator.reverseOrder()); // [4, 3, 1]

Comparable for natural/default order.

- Use Comparator for custom rules (like by length, reverse, etc).

Interview Questions and Tips

Questions (Covering All Topics)

- Annotations: What is

@Override? Give example. (Explain it checks overriding.) - Annotations: How to make custom annotation with runtime retention?

- RegEx: Write pattern for valid phone: (123) 456-7890.

- RegEx: Explain difference between greedy and lazy quantifiers.

- Threads: Difference between Thread and Runnable?

- Threads: What is synchronization? Why needed?

- Threads: Explain deadlock with example.

- Lambda: Write lambda for sorting list by length.

- Lambda: What is functional interface?

- Sorting: Difference between Comparable and Comparator?

- Sorting: How to sort objects by multiple fields?

Tips

- Practice code: Run examples on IDE like Eclipse.

- Understand basics first: Start with simple, then advanced.

- For interviews: Explain why (e.g., why synchronize? To avoid races).

- Common pitfalls: Forget to handle threads safely, complex RegEx.

- Read docs: Java API for details.

- Mock interviews: Time yourself explaining.

- Focus on Java 8+: Lambdas, streams are hot.